On a Tuesday morning in April 2017, Hinda Omar, a Somali outreach worker with the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH), learned that there were 3 children with measles in the Somali community. She recognized immediately that this could be a serious situation and affect many more children in the community. Vaccination rates for the MMR vaccine – which protects against measles, mumps and rubella – had been going down in the Minnesota Somali community over the last decade. This meant more people, especially children, were at risk of getting sick with measles.

As of June 19, 2017, there have been 78 cases of measles making this Minnesota’s worst measles outbreak since 1990. Most of the cases have occurred in the Somali community in the Twin Cities area and the vast majority of the cases were not vaccinated. In 2004, the Somali community had one of the highest vaccination rates for MMR vaccine. However, after 2006, families stopped vaccinating putting many at risk.

“I was worried about the community,” said Omar. “I knew the [vaccination] rates were low, and I was concerned. I did not know what an outbreak would look like in my community.”

Omar has been working with the MDH Immunization Program to educate the Somali community about the importance of vaccinations since 2014. In that time, she has learned a lot about why vaccination rates have dropped and the concerns families with unvaccinated children have.

“It is about fear and misrepresentation,” she said. “Parents have heard incorrect information about MMR vaccine and its links to autism. They are generally concerned about what to do.”

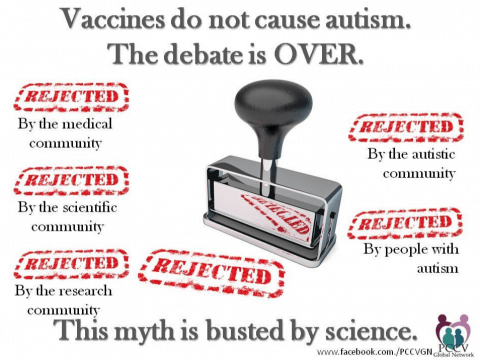

Anti-vaccine groups have been targeting the Minnesota Somali community for years. They have spread a lot of incorrect information and taken advantage of family’s fears of autism by telling them that vaccines cause it—particularly the MMR vaccine. This is not true. There is no scientific link connecting autism with vaccines like MMR.

Over 34,000 scientific studies have been done about autism since 1943. They have found that there are many causes of autism, such as genetics, injury to the brain, being born too early, and more. The studies have also found that autism usually occurs before birth or at birth.

“Autism can be frightening for families,” Omar said, “but there are services and interventions that are known to help children with autism succeed.”

All of the incorrect information from the anti-vaccine groups about MMR vaccine has clouded the judgement of parents. Omar said she knows parents want to do what is good for their children and has learned through her work that many thought they were doing the best thing for their child. “They were scared of autism and never knew that measles could be a very serious disease,” she said.

So far, 22 people have been hospitalized during this outbreak because they were severely sick. Measles can cause diarrhea, ear infections, pneumonia, or a brain infection called encephalitis that can lead to permanent brain damage. It can even cause death. Measles also causes long-term health consequences. For a couple of years after a person has measles, they are more likely to get sick with other diseases because their immune system is still recovering from fighting the measles virus.

Many of the children got sick with measles because they attended the same child care or school as another child that had measles. A person in the same place as someone who is sick with measles is considered exposed. Children who have not received the MMR vaccine are very likely to get sick with measles if they are exposed. Because a person can spread measles to others before they have symptoms, children who were exposed and were not vaccinated were asked to stay out of child care or school for about 3 weeks.

“This can be very hard for families if they have to miss work, but it is very important for stopping the spread of the disease in the community,” said Omar. “Children that were vaccinated are considered protected and do not have to stay out of child care or school if they were exposed to measles.”

Schools and child care centers play an important role in keeping children healthy and preventing the spread of disease. They should have records of every child’s vaccination history so they know who could be at risk of getting sick and would need to stay out of child care or school if they had a case of measles.

Parents also play a very important role in keeping the community safe. Omar and her colleagues at MDH want the community to know that they understand their fears and are ready to answer questions and share correct information about MMR and other vaccines. They also recommend that parents talk to their child’s health care provider if they have questions or want to schedule a time to get their child vaccinated.

“When something is in your heart, it is hard to change your head,” said Omar. “But I know in my heart that vaccination is the best thing for my family and my community. I will continue to have conversations with parents about the importance of MMR vaccine so that we don’t have to experience another outbreak like this.”

For more information about measles, go to www.health.mn.gov/measles.