Measles outbreak affects at least 30 in Minnesota, closes Somali religious school

The highly contagious virus has been spreading in child care centers, other gathering places, health officials said. They urged families to seek out vaccines ahead of the new school year.

A measles outbreak that began in May in Minnesota has spread to 30 people, primarily infecting children in the Somali community. One dugsi, or Islamic religious school, has voluntarily closed in order to curtail the spread, according to the Minnesota Department of Health.

About a third of the patients have required hospitalization, a state spokesperson said. All but one were unvaccinated.

The outbreak brings the state to measles 36 cases this year.

Measles is endemic in many countries, including African countries that Minnesota’s Somali families visit in the summer months. Seven people contracted the respiratory virus from travel, state health officials said.

“So when people who didn’t vaccinate and then travel outside of the country where measles is still existing, they contract it and then it spreads here because we have a close-knit community with big families,” said Sheikh Yusuf Abdulle, executive director of Islamic Association of North America. He has requested that people attending this weekend’s annual convention consider their vaccination status before attending.

“We’re concerned because 36 is a big number,” said Sheyanga Beecher, a certified nurse practitioner in pediatrics at HCMC and medical director of Hennepin Healthcare Mobile Health. “And, school’s around the corner. It’s been spreading a lot in child care centers, areas where people congregate. And next week kids are going to be congregating on buses, in classrooms, in hallways … so it has the potential to increase.”

No one wants their child hospitalized, she said, but the impact goes beyond hospitalizations: When a school closes or excludes unvaccinated students, parents often scramble to take time off of work or find child care.

What is measles and how does it spread?

Measles is a respiratory virus that can cause symptoms ranging from a cough, rash, fever, and runny nose to pneumonia and permanent brain damage. In 2022, the disease caused about 136,000 deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

“Measles isn’t innocuous,” Beecher said.

People often focus on the runny nose, cough, and rash, Beecher said, but some patients develop brain damage and a few contract a rare complication called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis that can lead to death years after the infection, she said.

Measles is also associated with miscarriage in pregnant people, said Munira Maalimisaq, a family nurse practitioner at Park Nicollet and the founder and CEO of Inspire Change Clinic.

“Most of them have not connected dots on how serious it is,” she said.

Measles spreads easily through the air, more readily than most respiratory viruses, lingering in a room hours after an infected person was there.

“Measles loves to seek out the vulnerable, those without protection, the unvaccinated,” said Lynn Bahta, a public health nurse at the Minnesota Department of Health who serves as the immunization program’s clinical consultant.

“When you get people in gatherings, it doesn’t take much and it can spread quickly,” she said.

And since the time from exposure to getting the disease can range from five to 21 days, longer quarantines are necessary when unvaccinated people are exposed to the virus, she said.

At least 95% of the general population needs to be vaccinated against measles in order to protect the remaining 5% because the disease is so contagious, Beecher said. The threshold is higher than it is for other diseases because measles is so contagious.

Why is the Somali community especially at risk?

The World Health Organization declared that the United States eliminated measles in 2000. But outbreaks can still occur. In 2017, an outbreak in Minnesota led to more than 70 cases, mostly in the Somali community. In 2022, the disease again spread locally after several people contracted measles while traveling.

The Somali community in Minnesota is especially vulnerable to these outbreaks for several reasons. Only 24% of Somali Minnesotan children born in 2021 had gotten the MMR vaccine by their second birthday, due to widespread disinformation about the safety of the vaccine and a decrease in routine well-child visits during the pandemic. In 2004, the rate was over 90%.

And Somali Minnesotans often travel to countries where the disease is endemic and access to vaccines is scarce, said Yusuf, the imam. Unfortunately, that travel often coincides with the end of summer, so kids are getting sick just as they’re heading back to school, he said.

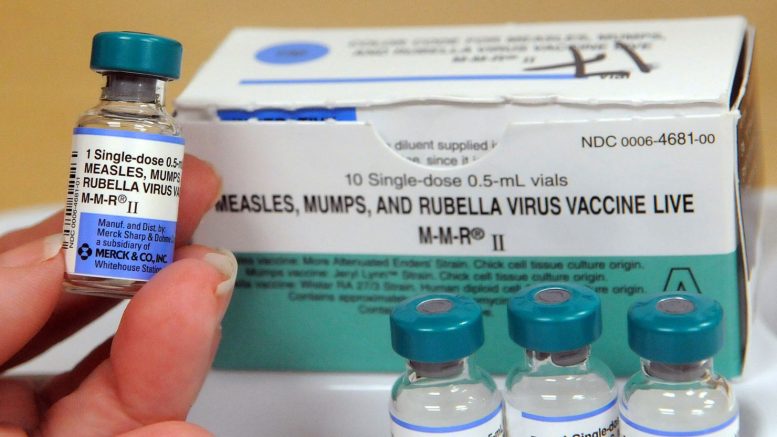

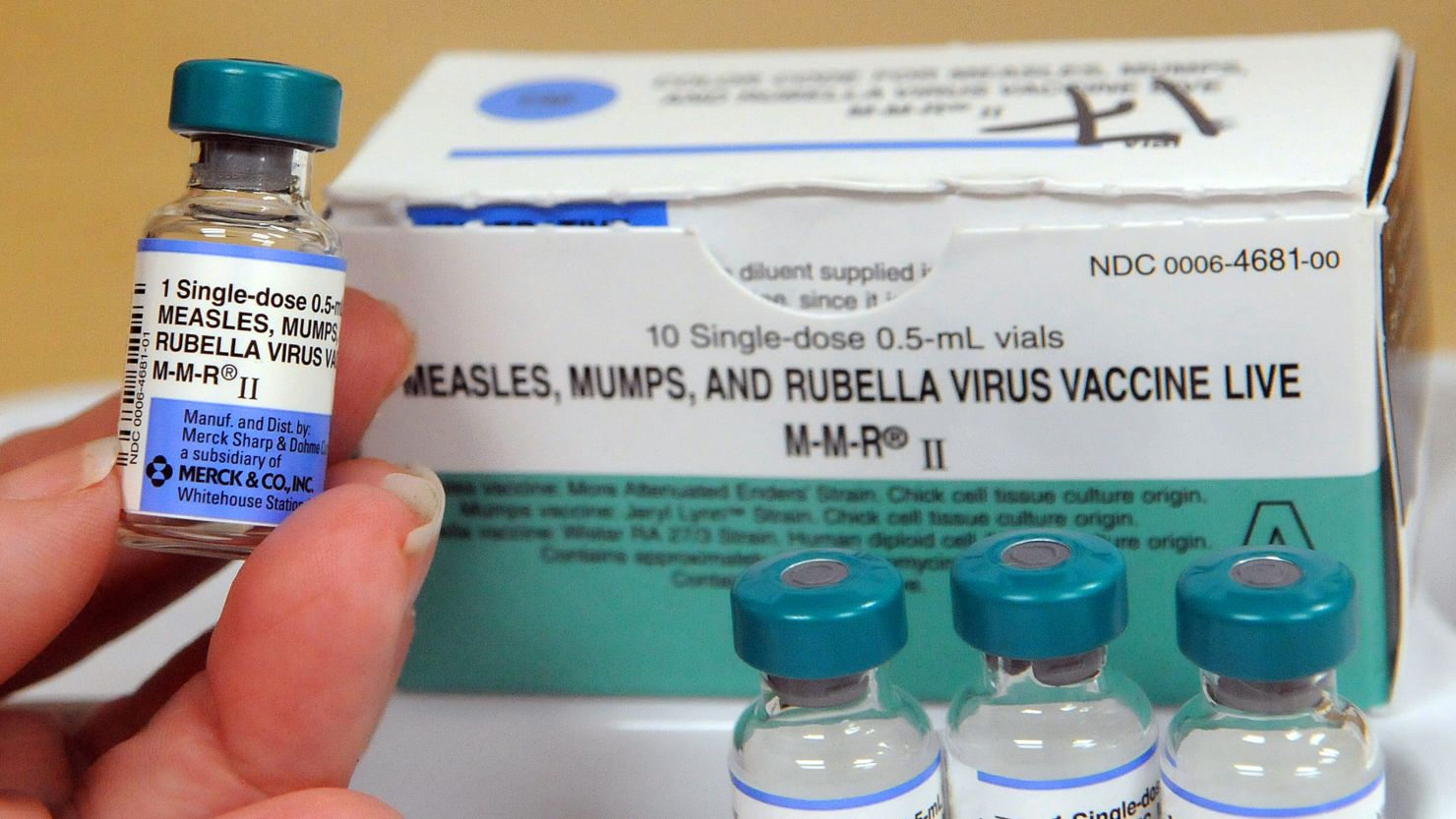

Like many vaccines, the measles vaccine is made from a virus that has been modified so that it is unable to cause infection. The MMR protects against measles, mumps, and rubella, three different viruses. Many people experience a fever and an achy arm for a day or two after getting the shot, Beecher said. Side effects can be treated with an over-the-counter painkiller such as acetaminophen.

Trust is key to increasing vaccination rates

The Minnesota Department of Health has prioritized connecting with the Somali community about measles since a 2011 outbreak resulted in 26 measles cases. That intensified during the 2017 outbreak. Health officials and health care providers said that everyone learned a lot about effective ways to promote vaccines from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Post-COVID, we have a strong community network of health care systems,” said Beecher, including mobile health care teams. “We have strong relationships with BIPOC community organizations and the education sector. So when there is an outbreak, we know who’s willing to support and it’s just a matter of plugging in people.”

Of course, increasing vaccination rates is a long-term effort that can’t be solved during an outbreak. But the key to increasing vaccine uptake, every health professional Sahan Journal interviewed said, is fairly simple: Providers need to listen to patients’ concerns and build trust.

Community members often feel judged, that the vaccine is being pushed on them, Maalimisaq said. If they feel their concerns are dismissed or marginalized, that’s a missed opportunity for education.

“They feel that they’re being shamed for not giving their children the vaccine, so they avoid well checks or find providers who are more understanding,” she said.

Families know that a discussion about vaccination will take place at an appointment, so their defenses are already up, said Jamila Abdukadir, a family nurse practitioner who works at the Axis Lake Street Clinic.

“So when I sit down with them, I listen to them and I let them guide the conversation,” she said. “There’a a point when they let their guard down, and express their fear and anxiety. That’s where I can come in and educate and give them my medical expertise and let them decide.”

Jamila, who grew up in Somalia, said she often points out that the Quran tells people to seek guidance from others better educated in a topic. In one instance, after a woman shared a specific concern about the vaccine, Jamila opened her phone and showed the woman her own personal vaccination record.

“I showed her that as a health worker, I have all of this so I don’t give you the diseases — and she took the vaccine. It’s the simple thing of understanding where the fear is coming from,” she said.

Such conversations can take an entire visit, Beecher said. But when a family says, “let’s do it” at the end of the appointment, “it’s a huge win.”

Community members have been inundated with false information. But not all of the misinformation comes from bad actors, said Dr. Taj Mustapha, who leads equity strategy at M Health Fairview.

“A lot is from people who are trying to do their best — they hear a thing, and they only hear part of it and it becomes like the telephone game kids play where you whisper into the next person’s ear,” she said.

That’s why trusted medical experts are so important, she said. Earning trust can be easier when health care providers look like their patients and speak the same language, Jamila said. It’s also important to hear the message from other community members.

Najma, a Minneapolis mother who works as a licensed practical nurse, shares her story about vaccinating her children at outreach events — including the Somali Children’s Health Fair at the Park Nicollet Clinic Minneapolis, which runs noon to 4 p.m. this Saturday.

After she vaccinated her first two children, Najma developed reservations when her third child was diagnosed with autism. But when another child was born, they were also diagnosed with autism — despite not having been vaccinated.

She sought out expertise at Inspire Change, the clinic that Maalimisaq started..

“I felt they would understand where I was coming from, and they were incredibly compassionate,” she said.

Her six children are now fully vaccinated and she works to debunk myths around vaccines and autism.

Yusuf shares a similar story of deciding to vaccinate his children after an unvaccinated son was diagnosed with autism.

“Families need to share their stories to make sure kids are vaccinated,” he said.

Despite positive results from individual conversations and increased collaboration among health care entities, reversing the trend is an uphill battle, Mustaphe said, as trust in institutions has decreased.

“We’re swimming upstream,” she said.